(When) Is Mechanistic Interpretability Identifiable?

I. Introduction

I recently finished a paper, “Characterizing Mechanistic Uniqueness and Identifiability Through Circuit Analysis,” alongside a group of 3 others and a mentor, and I’m very happy with the final output which is posted at this link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HY69UUKOwcNAXDW00ICmzNy_Zq2wQ2yl/view?usp=sharing. The point of this post is to discuss both the background and methodology of the paper, as well as to provide some reflections over things we couldn’t fit in the 9 pages. Some of the text here will be taken directly from the paper, whereas the rest will just be an informal discussion. For a TL;DR summary, feel free to glance at the abstract at the link provided!

Mechanistic Interpretability seeks to reverse-engineer the internal representations and algorithms that produce model behaviors. MI has two main motivations. Intrinsically, many find interest in interpretability research for the sake of knowing more about AI systems. For this reason, many in the community seem to find it pointless given how difficult it is to produce truly accurate, generalizable MI findings. Extrinsically, interpretability carries implications for safety and alignment efforts: if we can trace a model’s chain-of-thought and why it took that path, we can understand and impute unwanted behaviors.

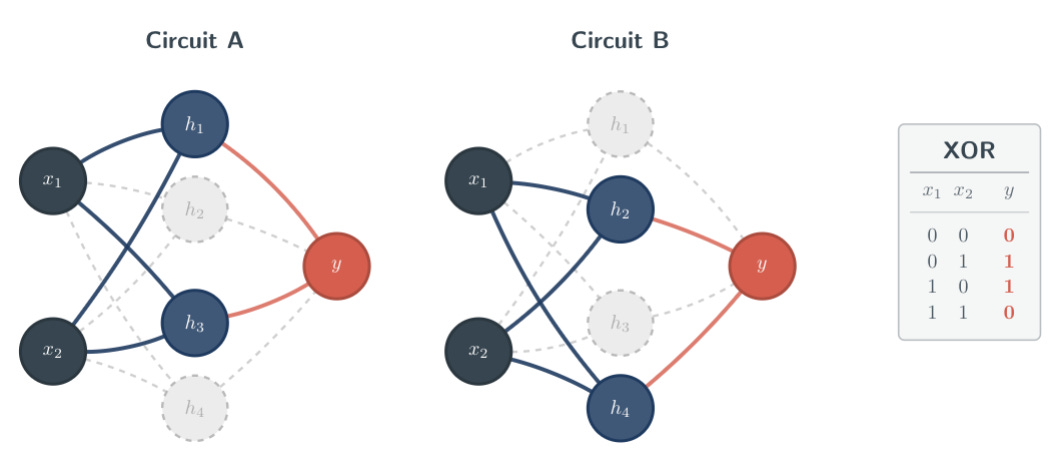

A key method for interpreting a neural network’s behaviors is through the lens of a ‘circuit.’ Circuits are subgraphs of a neural network’s nodes and edges that can independently complete a task or sub-task. In a typical multi-layer perceptron, a circuit may consist of neurons and their connecting weights that complete, for instance, addition. Knowing this makes it easier to understand the rest of the content here.

Recent work (Meloux et al., 2025) found that, in some neural networks, multiple circuits can complete the same input-output mapping, which they termed ‘non-uniqueness’. This introduces a problem with identifiability: if one is unable to pinpoint the origin of all of a neural network’s behaviors, that neural network’s behaviors are ‘non-identifiable.’ They viewed non-identifiability as a problem with non-unique circuitry, since a circuit definitionally is a location within the network responsible for a given behavior. The concept of non-identifiability that the above paper studied was first introduced by Meloux in 2025, but redundant components have been observed in both biological and artificial neural networks.

The discussion within Meloux et al.’s paper does a pretty good job at going over whether or not identifiability is necessary. The answer depends on our goals:

Explainability: If our main goal is explainability, then identifiability is probably beneficial, because if we can’t determine the origin of a network’s emergent behaviors (i.e. deceptive alignment), that’s definitionally un-explainable.

Faithfulness: if our main goal is to make AI models as close to modelling humans as possible, non-identifiability is a feature, and not a bug. Redundancy is ample within biological neural networks, and as networks achieve higher representational capacity, we can’t possibly ensure every neuron completes a different task.

Meloux et al. gave strong evidence that non-identifiability is an issue within neural networks, but they didn’t characterize when non-identifiability or non-unique circuits may arise. As such, we chose to research this issue and lay a preliminary framework to characterize non-uniqueness.

II. Methodology

I’ll be brief here. As a setup for our experiments, we used a 2-4-1 multi-layer perceptron (2 input neurons, 4 hidden-layer neurons, 1 output neuron) trained on the Boolean XOR task. The use of a small ‘toy’ MLP made the process of circuit enumeration and validation much easier. The Boolean XOR task was convenient due to its synthetic, simple, and non-linear nature. Note that while we did vary the hidden-layer width and tasks during experimentation, the above specifications were the base scenario.

The criteria by which we enumerated and evaluated circuits was very specific, so I’ll copy the text from the paper itself:

For each trained model, we enumerate all admissible subsets of nodes and edges consistent with the constraints described above. For each candidate circuit, we construct the corresponding ablated model—the isolated circuit independent of all other network components—and evaluate it on the full validation dataset. We treat a circuit as valid when the ablated model matches the full model’s output with a mean squared error below 5%. This criterion allows small deviations while ensuring the circuit maintains functional equivalence to the original model. Our conception of a valid circuit also corresponds to a sufficient sub-graph.

Complete enumeration is feasible only for small architectures because the number of possible solutions grows exponentially with the number of parameters. Hence, all enumeration experiments are restricted to models with limited width and depth (unless otherwise noted).

To encapsulate, we identify circuits through the following process:

Enumerate all possible subsets of nodes & edges in the trained model and construct the corresponding ablated model for each subset.

Evaluate the ablated model on the full validation dataset.

Declare a circuit as valid if the ablated model achieves near perfect accuracy on validation set, which we define here as a mean squared error below 5%

III. Results

More comprehensive specifications for each experiment can be found in the paper, but here are the three experiments that made it to the paper. I’ll be pretty cursory here, since a better description can be found in the paper. The purpose of this section is to provide a simpler explanation/background of the experiments there.

I. Induced Sparsity

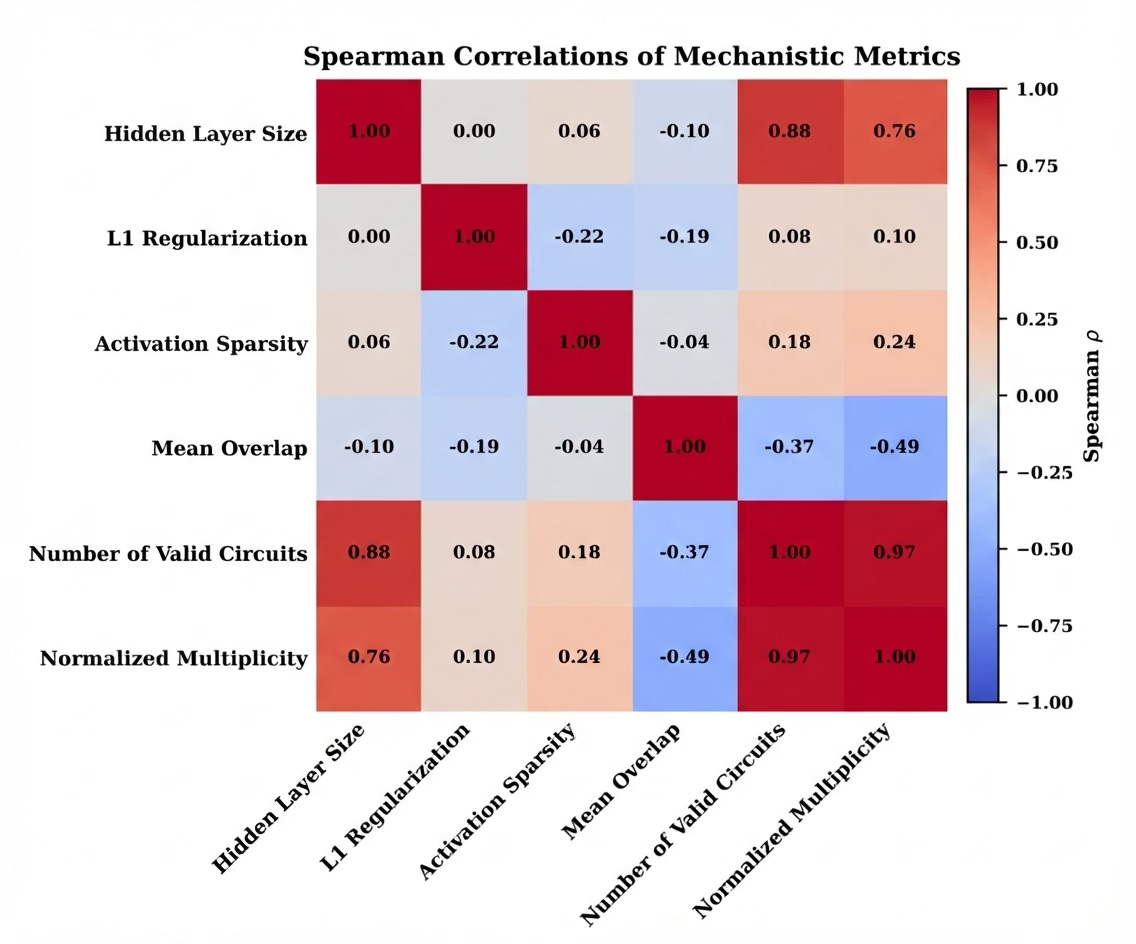

‘Sparsity’ is a condition of the weights and biases of a network where a high percentage of a model’s parameters are 0. The goal is to prune unnecessary weights, which can theoretically make the model more efficient. Theoretically, if multiple neurons or circuits are completing the same input-output mapping, sparsity constraints (such as L1 Regularization) should bring the unnecessary, extra weights to 0. Counterintuitively, we found that L1 regularization actually showed a weak correlation with promoting unique circuits.

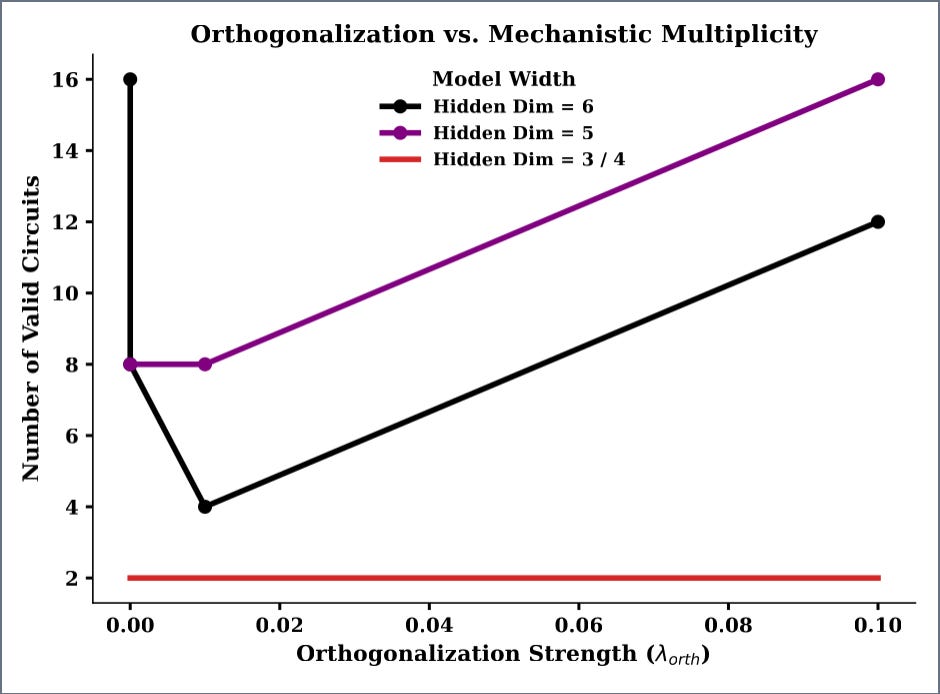

II. Orthogonality

Orthogonality, like L1 Regularization, is another artificial inducement applied to the network’s activations. Broadly, orthogonality refers to two vectors being perpendicular to each other, or ‘linearly independent.’ In deep learning, orthogonality penalties encourage the model’s representations to be diverse and non-redundant, pushing neurons to respond to distinct features rather than overlapping ones, or to be ‘independent’. We also expected orthogonality to show a strong correlation with uniqueness, but we found that activation orthogonality penalties showed a weak correlation with uniqueness, and they occasionally even promoted non-uniqueness.

III. Model Capacity

Model capacity, in this context, refers to the number of neurons and connecting weights in a network. Models with more neurons and weights have a higher ‘capacity,’ since they can represent more features. Intuitively, a model with higher capacity being trained on the same task as a smaller model should have more non-unique circuits, because it can represent more features. This experiment tested that hypothesis, and the results followed the trend we expected, showing a strong, positive correlation between model capacity and non-uniqueness.

The paper includes a discussion about the ‘effective rank’ of a task, but that experiment was downstream of the model capacity experiment, so I’ll avoid spending time talking about effective rank here.

IV. Reflection

This project showed us how uncertain and unexpected interpretability results can be. We went into this project under the strong assumption that L1 regularization and orthogonality constraints would be the largest stimulants for uniqueness, but ultimately found that the correlation was weak, and sometimes went the other way. This would seem to reinforce the idea that, due to the noise inherent in neural networks, interpretability research efforts should be incremental and build off of established concepts to avoid investing time into overly ambitious projects.

Finally, I wanted to jot down a few general things I learned:

Writing is thinking. Many of the ideas our group came up with were formed during the writing process itself, not while scrolling through google search results. Writing forces you to think in a structured manner and communicate your ideas properly. This short article goes more in-depth on this topic: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44222-025-00323-4

If you throw darts with a blindfold, one of them will (probably) hit. This is a bit of a hyperbole, but the point still stands that you can’t continuously iterate over ideas until you find one that is perfect and ‘fool-proof’. You will likely never find that ‘perfect’ idea, and eventually, you need to take action.